In my opinion, the best of the St. Lucia rums hailing from the eponymous distillery

We choose friends for many reasons: in my case it’s a question of what quality they add to my overall existence and what I can contribute to theirs. I may not like everything about them, or they about me (admittedly, I occasionally piss people off, sometimes just by being in the same room breathing the air they’d rather be smoking) – yet all my friends are interesting, all have quirks and characters that are appreciated and savoured. I feel the same way about rums – they may not be the best at what they try to be, but if they go for the fences with cheerful abandon, well…how can I not appreciate that?

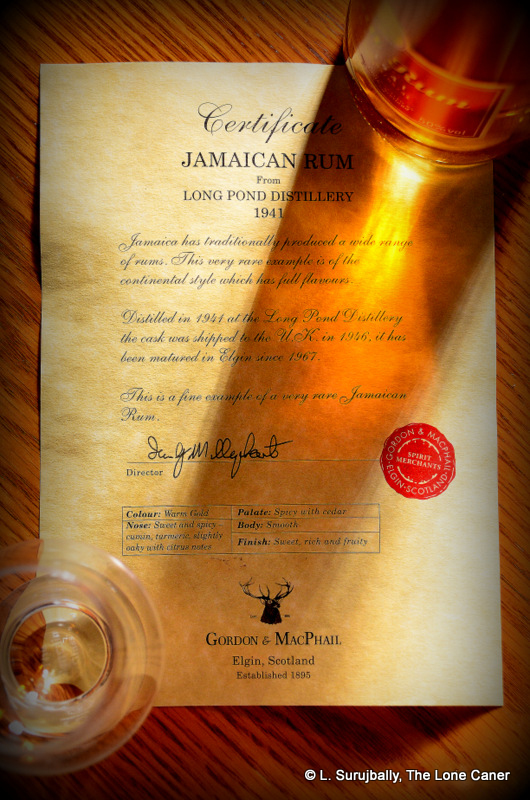

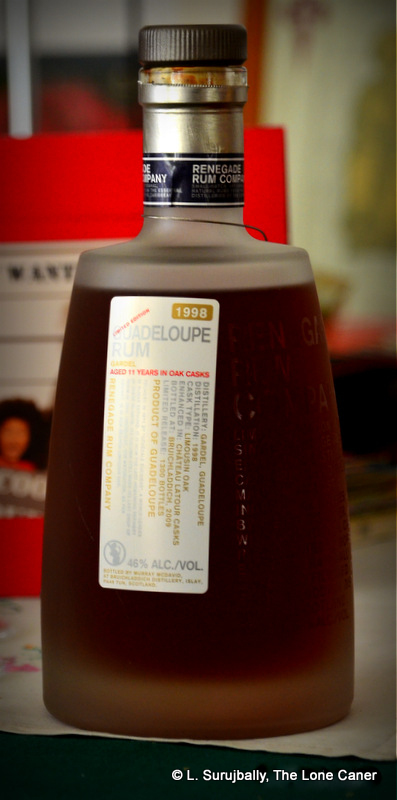

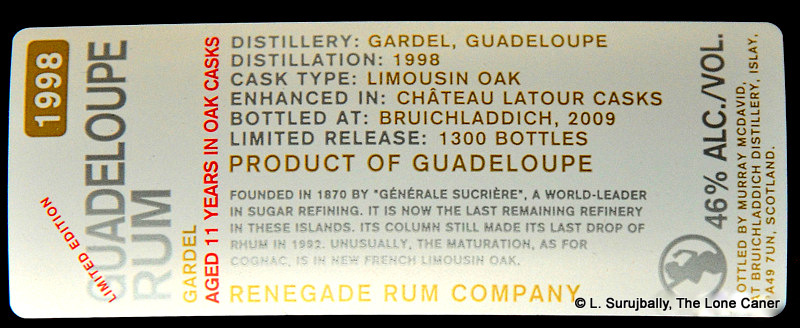

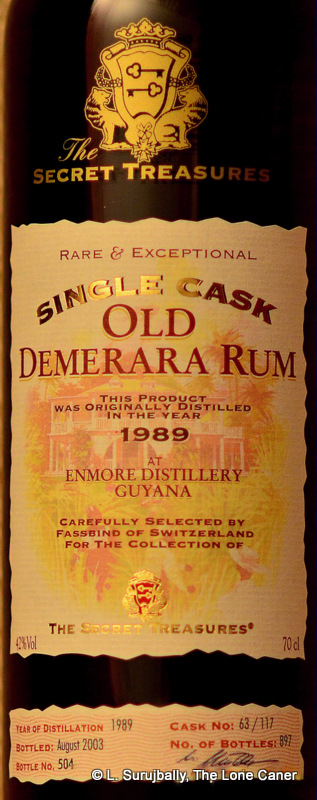

Renegade Rums are a subset of what I term “series rums” (like the Rum Nation, Secret Treasures, Bristol and Plantation series, for example – in years to come they came to be called independent bottlers) with which I have had a love-hate relationship since I first began trying them four years ago. Some were too much like whisky, others were not aged enough, in some cases the finish just didn’t work (for me – others may differ in their assessments), and in yet others it seemed like they weren’t loved enough by the maker. In other cases they succeeded swimmingly

The Renegade St. Lucia 1999 10 year old was firmly in that last camp. Bottled at a pleasant, tongue-titillating 46% and presented in that frosted, etched bottle I’ve always sighed over, it was distilled ina double retort pot still, aged for ten years in used Bourbon casks and then finished (for three months, I think) in Chateau LaFleur casks, which provided something of a fruity Bordeaux hint to the final profile. It was probably this which made me appreciate it more: quirky it might have been, but I couldn’t argue with the originality.

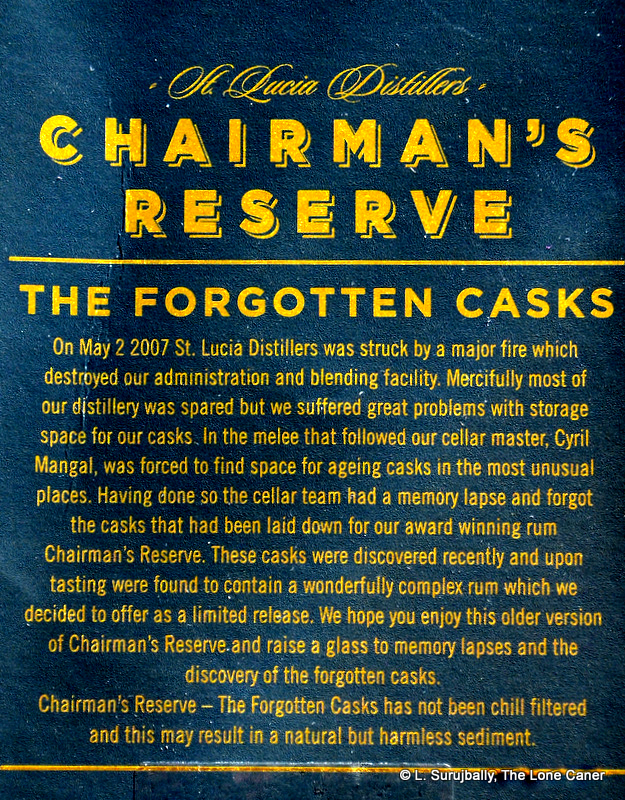

The amber, medium bodied rum was the lightest-coloured of the rums hailing from St Lucia which I tried (Forgotten Casks, Admiral Rodney and the 1931), and right away after decanting it leaped up and stabbed me in the nose with the now familiar pitchfork of Renegade’s slight overproofishness (is that a word?). Plasticine, rubber and play-dough were evinced right out of the gate – not aromas I particularly cared for, but bear with me, reader: stay with it. I had a similar experience with the Rum Nation Jamaica 25 and 1985 Demerara 23, and you gotta let that sucker breathe a bit. Do that and the next wave comes over the beachhead…smokiness, cherries, sweet breakfast spices, nougat, well-polished leather and aromatic pipe tobacco in an antique tobacconists shop found in an old European capital, along a well hidden cobbled street on a blustery day in autumn.

The taste followed right along, heated, yes, just not overbearing and mean. It wasn’t the smoothest of sipping quality rums, no – strength and youth showed in a slight bite for which I marked it down, and it had a dry tang and brininess that at first startled me – but the rum was decently aged, there was a woody backdrop to which was gradually added salt water taffy, candy, caramelized apples…plus cherries and apricots, all held in balance and harmony by scorched pine wood. Coiling around all of these sumptuous tastes were notes of Russian or black china tea…lapsang-suchong. I mean, this was just heavenly, especially since the relative youth of the rum made it spry and agile and almost mischievous, without the deep, mellow ponderousness of grandfathers (in rum years) like, oh, the Panamonte XXV or the El Dorado 25. The long finish was similarly good, exiting in the leisurely, sauntering fashion of a prima donna who knows she’s good, leaving behind the memory of salty biscuits and marzipan.

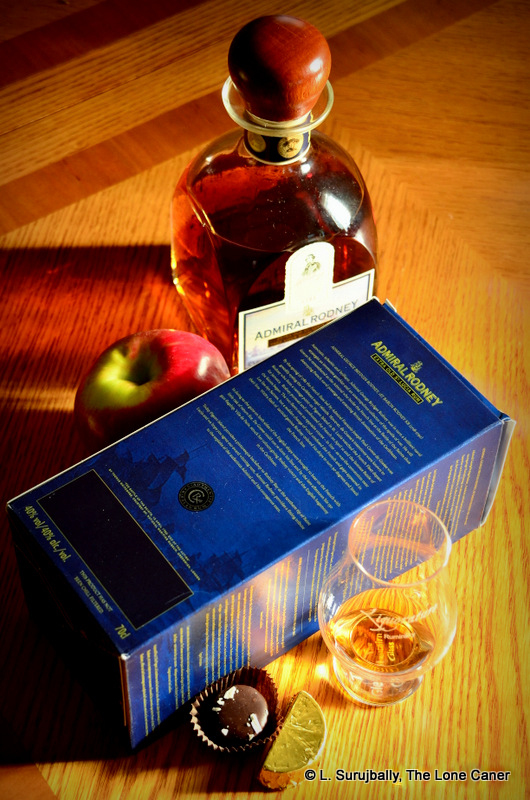

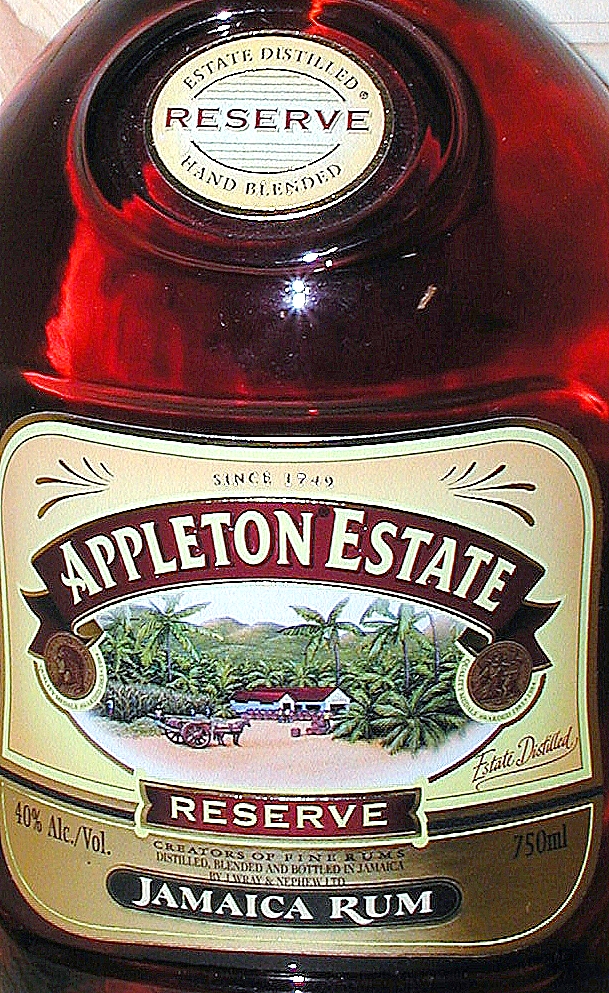

All three of St. Lucia Distillers rums scored within a few points of each other, weaknesses and low scores in one area recouped by strengths in another. Tough to choose between them all, yet, at end, I absolutely preferred the Renegade version of St Lucia’s rums to any of the others, good as they were. What it came down to was a question of character. The Admiral Rodney and 1931 were solid well-made rums: they merely hewed so closely to the line that some of the characteristics of playful experimentation were lost. For sheer originality, for sheer joy and exuberance and verve, for complexity and interesting profile, the Renegade had it.

(#133. 83.5/100)