Originally published November 2020. Continuously updated, with the last edit in June 2023

Introduction

More and more resources are coming online even as – or perhaps because – an increasing amount of people, young and old and in between, are coming into rum. They arrive new, or from some other spirit, and are wont to inquire “Where can I find out about…?” The questions are always the same and after more than ten years of doing this, I sometimes think I’ve seen them all:

- What rum do I start with?

- If I like this, what would you recommend?

- What’s the sugar thing all about?

- How much?

- What’s it worth?

- Where can I find…?

- What to read?

- How? Where? When? Why? What? Who?

Several years ago (February 2016 for those who like exactitude), Josh Miller of Inu-a-Kena, who was one of the USA’s premier reviewers before he turned to other (hopefully rum-related) interests and let his site slide into a state of semi-somnolence, published an article called “Plugging into the Rum World.” This was a listing of all online resources he felt were useful for people now getting into the subculture.

Five years on, that list remains one of the only gatherings of material related to online rum resources anyone has ever bothered to publish. Many bloggers (especially the Old Guard) put out introductions to their work and to rum and just about all have a blogroll of favoured linked sites as a sidebar, and I know of several podcasts which mention websites people can use to get more info – it’s just that they’re scattered around too much and who has the time or the interest to ferret out all this stuff from many different locations?

Moreover, when you just make a list of links, it does lack some context, or your own opinion of how useful they are or what they provide. That’s why I wished Josh’s list had some more commentary and narrative to flesh it out (but then, as has often been rather sourly observed, even my grocery list apparently can’t be shorter than the galley proofs for “War & Peace”).

Anyway, since years have now passed, I felt that maybe it was time to kick the tyres, slap on a new coat of paint and update the thing. So here is my own detailing of all online and other resources I feel are of value to the budding Rum Geek.

(Disclaimer: I am not into tiki, cocktails or mixology, so this listing does not address that aspect of the rumisphere).

General – Social Media and Interactive Sites

General – Social Media and Interactive Sites

For those who are just starting out and want to get a sense of the larger online community, it is strongly recommended that one gets on Facebook and joins any of the many rum clubs that have most of the commentary and fast breaking news. There’s an entire ecosystem out there, whether general in nature or focused on specific countries, specific brands or themes.

Questions get asked and get answered, reviews get shared, knowledge gets offered, lists both useful and useless get posted, and fierce debates of equal parts generosity, virulence, knowledge, foolishness, intelligence and wit go on for ages. It’s the liveliest rum place on the net, bar none. You could post a question as obscure as “Going to Magadan, any good rum bars there?” and have three responses before your ice melts (and yes I’ve been there and no there aren’t any).

The big FB Rum Clubs are:

Other general gathering points:

More specialized corners of the FB rum scene are thematic, distillery- or country-specific, or “deeper knowledge-bases”. Many are private and require a vetting process to get in but it’s usually quite easy. (NB: After a while you’ll realize though, that many people are members of many clubs simultaneously, and so multiple-club cross postings of similar articles or comments are unnecessary).

…there’s tons more for specific companies but those are run by industry not fans and so I exclude them. Too there are many local city-level rum clubs and sometimes all it takes is a question on the main fora, and someone in your area pops up and says, “yeah, we got one…”

The other major conversational forum-style resource available is reddit, which to me has taken pride of place ever since the demise of the previous two main rum discussion sites: Sir Scrotimus Maximus (went dark) and the original Ministry of Rum (got overtaken by Ed Hamilton’s own FB page). Somewhat surprisingly, there are only two reddit fora thus far, though the main one links to other spirits and cocktail forums.

The other major conversational forum-style resource available is reddit, which to me has taken pride of place ever since the demise of the previous two main rum discussion sites: Sir Scrotimus Maximus (went dark) and the original Ministry of Rum (got overtaken by Ed Hamilton’s own FB page). Somewhat surprisingly, there are only two reddit fora thus far, though the main one links to other spirits and cocktail forums.

/r/rum This is the main site with over 41,000 readers. Tons of content, ranging from “Look what I got today!” to relinked articles, reviews and quite often, variations on “Help!” Conversations are generally more in depth here, and certainly more civilized than the brawling testosterone-addled saloon of FB. Lots of short-form reviewers lurk on this site, and I want to specifically recommend Tarquin, T8ke, Zoorado, SpicVanDyke and the LIFO Accountant. Both the question “What do I start with?” and the happy chirp “Look what I got!” are most commonly posted on this subreddit.

/r/RumSerious (Full disclosure – I am the moderator of the sub). Created in late 2020, the site is an aggregator for links to news, others’ reviews and more focused articles. Not much serious discussion going on here yet but I continue to live in hope.

/r/tiki Lots of rum subjects turn up here and it’s a useful gathering place for those whose interests in tiki and rum intersect.

I’m deliberately ignoring other social media pipelines like Instagram and Twitter because they are not crowdsourced, don’t have much narrative or commentary, and focus much more on the individual. Therefore as information sources, they are not that handy.

Reviewers’ Blogs & Websites

On my own site I subdivide reviewers into those who are active, semi-active and dormant — here, for the sake of brevity, I’ll try to restrict myself to those who are regulars and have content going up on a fairly consistent basis.

Reviewers

WhiskyFun (France) – Serge Valentin is the guy who has written more reviews about rum than anyone in the world (he’s also done almost 16,000 whisky tasting notes but that’s a minor distraction, and a sideline from his unstated, undeclared true love of rums) in a brutally brief, humorous, short-form style that has been copied by many other reviewers.

WhiskyFun (France) – Serge Valentin is the guy who has written more reviews about rum than anyone in the world (he’s also done almost 16,000 whisky tasting notes but that’s a minor distraction, and a sideline from his unstated, undeclared true love of rums) in a brutally brief, humorous, short-form style that has been copied by many other reviewers.- Rum Ratings – This is a user-driven populist score-and-comment aggregator. From a reviewer’s ivory-tower perspective it’s not so hot, but as a barometer for the tastes of the larger rum drinking population it can’t be beat and shows why, for example, the Diplo Res Ex remains a perennial favourite in spite of all the negative reviews.

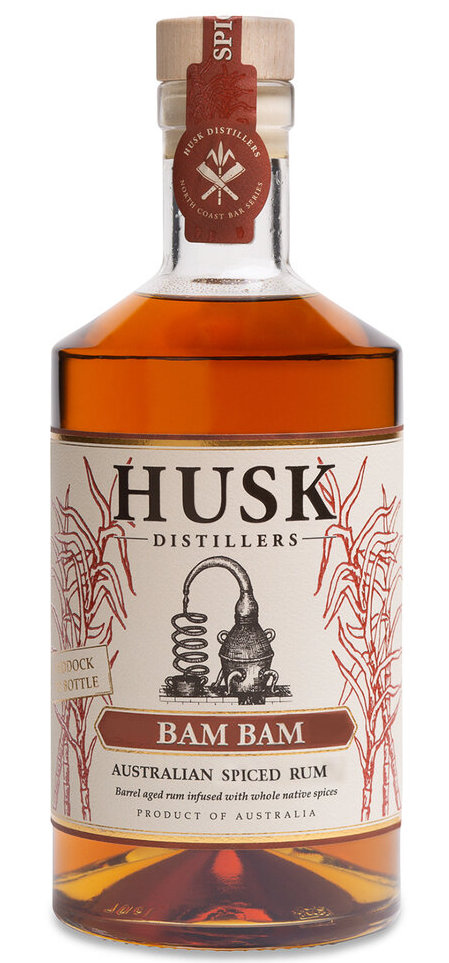

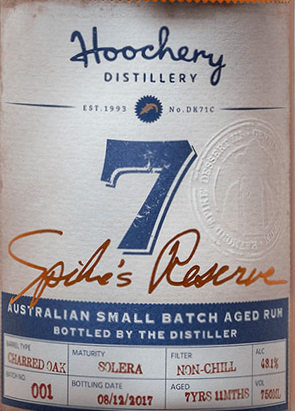

The Rum Barrel Blog (UK) – Barman Alex Sandu used to post his reviews directly into FB until he gave in and opened a site of his own. This guy posts mainly reviews, and he’s quite good, one of those understated people who will turn up a decade from now with a thousand tasting notes you never knew were there.

The Rum Barrel Blog (UK) – Barman Alex Sandu used to post his reviews directly into FB until he gave in and opened a site of his own. This guy posts mainly reviews, and he’s quite good, one of those understated people who will turn up a decade from now with a thousand tasting notes you never knew were there.- Single Cask Rum – Marius Elder does short form reviews of mostly the independent bottlers’ scene. What he posts is amazing, because he does flights — of similar bottlers, similar years, similar geographical places — to make comparatives clear, and the bottles in those flights are often a geek’s fond dream.

The Rums of the Man With the Stroller (French) – Laurent Cuvier is more a magazine style writer than a reviewer, yet his site has no shortage of those either, and he serves the French language market very nicely. Plus, all round cool guy. The poussette has been retired, by the way.

The Rums of the Man With the Stroller (French) – Laurent Cuvier is more a magazine style writer than a reviewer, yet his site has no shortage of those either, and he serves the French language market very nicely. Plus, all round cool guy. The poussette has been retired, by the way.- Le Blog a Roger (French) – Run by a guy whose tongue-in-cheek nom-de-plume is Roger Caroni, there’s a lot more to his site than just rums…also whiskies and armagnacs. Good writing, brief notes, nice layout.

Who Rhum the World? (French) – Oliver Scars does like his rums, and writes about the top end consistently and well, especially the Velier Caroni and Demerara ranges.

Who Rhum the World? (French) – Oliver Scars does like his rums, and writes about the top end consistently and well, especially the Velier Caroni and Demerara ranges.- Barrel Aged Thoughts (German) – A site geared primarily towards independents, and a strong love of Caronis, Jamaicans and Demeraras. Nicely long form type of review style.

- John Go’s Malternatives – John, based in the Philippines, writes occasionally on rum for Malt online magazine. Good tasting notes — and its his background narrative for each rum that I really enjoy and which will probably remain in the memory longest.

- Whisky Digest (FB) – Now here’s a gentleman from Stuttgart who eschews a formal website, and whose tasting notes and scores are posted on FB and Instagram only. Crisp, witty, informative, readable mini reviews, really nice stuff. Love his work. Also posts reviews on Instagram, which is unusual for written work.

88 Bamboo is an interesting website that was started around 2020 by two whisky guys in Singapore to concentrate on…well, whisky. As luck would have it they allowed guest posts from time to time, and one gentleman, Weixiang Liu, a cheerfully self-proclaimed “coffee brewologist and occasional rum addict,” started to pen some short rum reviews (about 70+ are on the site, most of them his). The writing is nice and the selections are well done.

88 Bamboo is an interesting website that was started around 2020 by two whisky guys in Singapore to concentrate on…well, whisky. As luck would have it they allowed guest posts from time to time, and one gentleman, Weixiang Liu, a cheerfully self-proclaimed “coffee brewologist and occasional rum addict,” started to pen some short rum reviews (about 70+ are on the site, most of them his). The writing is nice and the selections are well done.- Secret Rum Bar out of the UK does flights and single reviews and is really quite informative. This kind of work almost requires the short form approach to writing, and Stuart, the showrunner, is an engaging blogger with interesting rums to look at, every time.

- Malt Runners is a new site that opened in June of 2023, and is a curated collection of reviews – mostly whisky but also with a strong rum component – that were and are all written and posted first on reddit. These are all shortform pieces, and because of the multiple authors involved (mostly from USA/Canada), it is sure to be one of the best resources for quickie reviews that consumers can consult without wading through acres of turgid prose (y’know, like mine). LifoAccountant, mentionerd elsewhere here posts under the handle The Auditor on this site.

Others

Rum Revelations (Canada) – Occasional and valuable content by Ivar de Laat out of Toronto, who is usually to be found commenting on FB’s various fora and who runs the Rum Club Canada FB group. The gentleman has strong opinions, so you’ll never be in doubt what he likes or dislikes.

Rum Revelations (Canada) – Occasional and valuable content by Ivar de Laat out of Toronto, who is usually to be found commenting on FB’s various fora and who runs the Rum Club Canada FB group. The gentleman has strong opinions, so you’ll never be in doubt what he likes or dislikes.- Rumtastic (UK) – “Another UK Rum Blog” his website self-effacingly says, and he modestly and deprecatingly considered himself a merely “awesome, ace, wicked dude” in a comment to me some time ago. Short, brief, trenchant reviews, always good to read.

- Master Quill (Holland) – Alex and I are long correspondents and I always read his reviews of rum, which take second place to his writing about whiskies, but are useful nevertheless. Like most European bloggers, he concentrates mostly on the independents.

- Québec Rhum – This large Francophone Canadian site is unusual in that it is actually more like a club than a single person’s interests the way so many others on this list are: within it reside rum reviews, distillery visits, master class programs and some cost-defraying merchandise. For my money, of course, it’s the reviews that are of interest but it certainly seems to be the premiere rum club in Canada, bar none.

- Rum Shop Boy (UK) – Simon’s Johnson’s excellent website of rum reviews. Personal issues make him less prolific than before: in 2022 he began to post again, so here he is.

- Rum Diaries Blog (UK) – Busy with work these days, great content and reviews, some of which are quite in-depth. Mostly posts on FB but has resumed a limited posting schedule in late 2022, and the work is really quite excellent.

- The Fat Rum Pirate (UK) – Wes Burgin was the second most prolific writer of rum reviews out there (Serge remains the first). The common man’s best friend in rum, with strong opinions – you’ll never be in doubt where he’s coming from – and tons of reviews. He’s slowed down some as of 2023 and is almost dormant these days

Dormant Sites With Good Content

Du Rhum (French) – Cyril Weglarz is a fiercely independent all rounder, writing reviews, essays and even a book (The Silent Ones, see below). He’s noted for taking down Dictador and other brands for inclusion of undeclared additives and remains the only blogger – ever – to have sent rums for an independent laboratory analysis, over and beyond using a hydrometer.

Du Rhum (French) – Cyril Weglarz is a fiercely independent all rounder, writing reviews, essays and even a book (The Silent Ones, see below). He’s noted for taking down Dictador and other brands for inclusion of undeclared additives and remains the only blogger – ever – to have sent rums for an independent laboratory analysis, over and beyond using a hydrometer.- Roob Dogg Drinks is run by Toronto-based Reuben Virasami, whose family hails from Guyana. The site went live in January 2021 and posts remain intermittent, but always well written and informative.

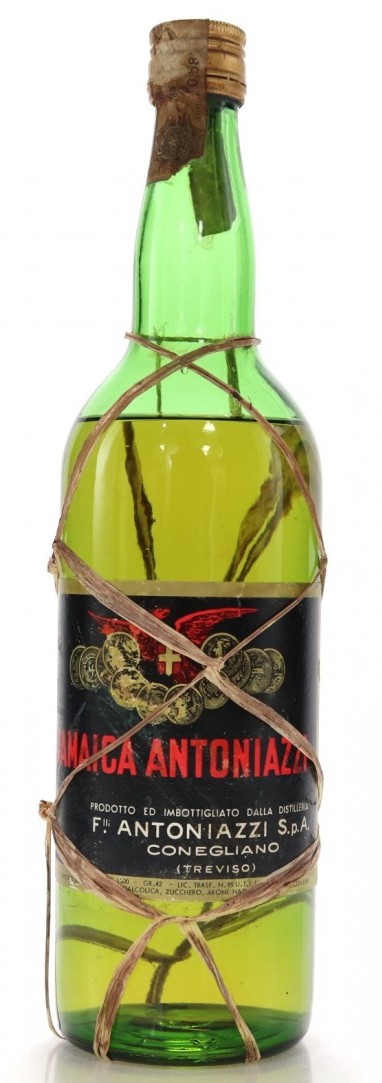

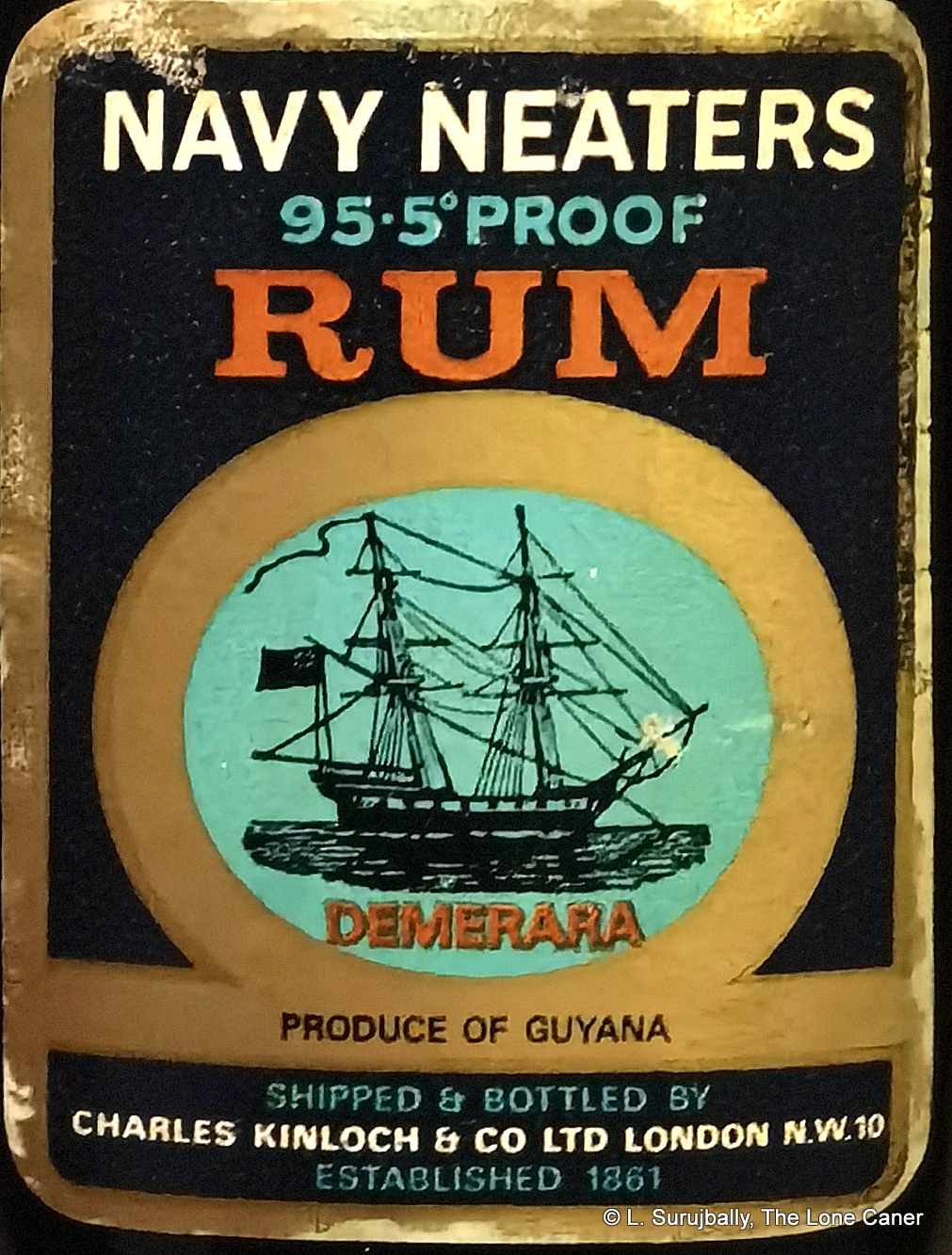

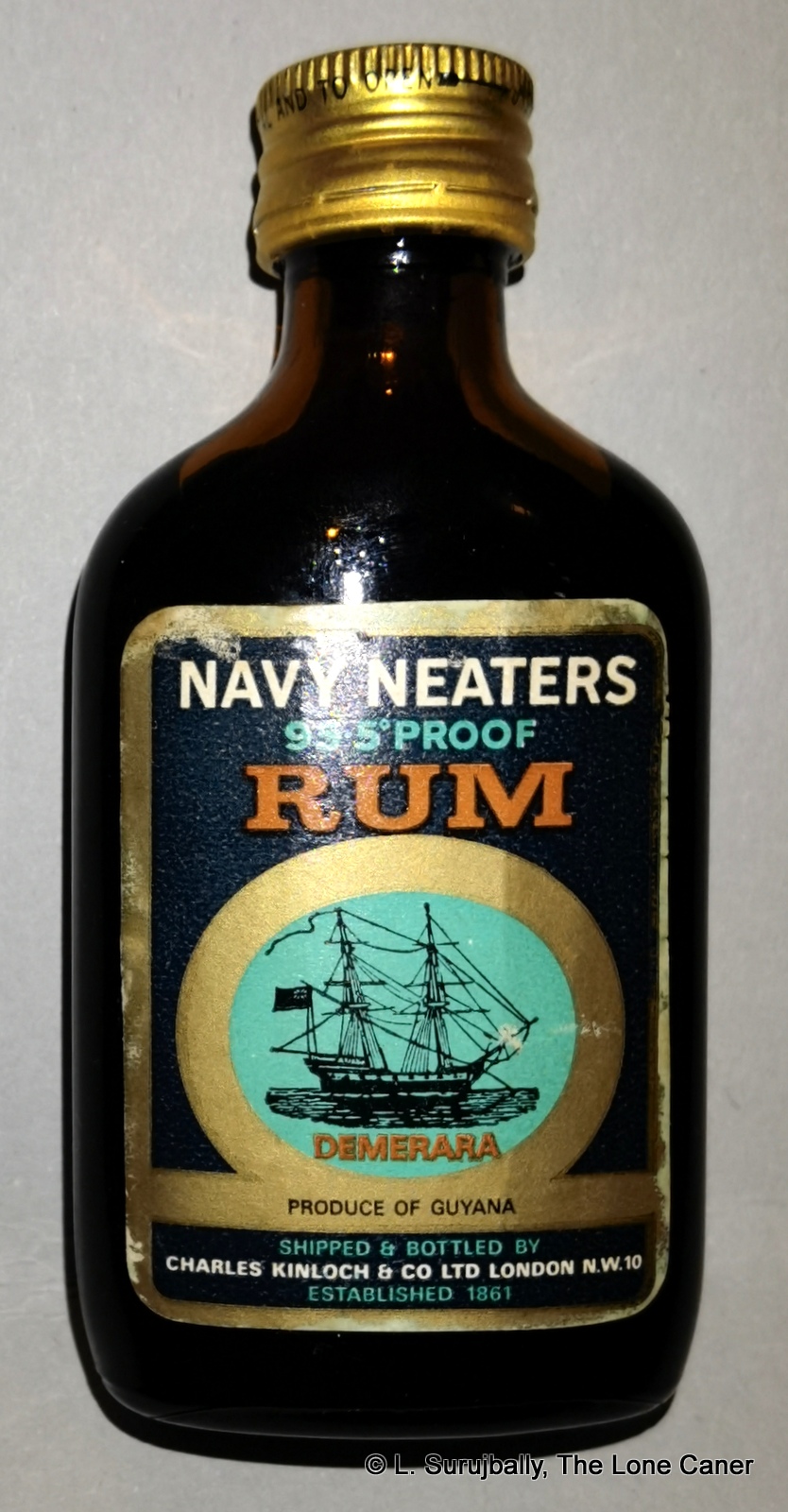

Rum Gallery (USA) – no longer updated for some years, I include it for the back catalogue, because Dave Russell has been active on the review since before 2010 and so has many reviews of rums we don’t see any more, as well as those from America.

Rum Gallery (USA) – no longer updated for some years, I include it for the back catalogue, because Dave Russell has been active on the review since before 2010 and so has many reviews of rums we don’t see any more, as well as those from America.- Rum Howler Blog (Canada) – Chip Dykstra reviews out of Edmonton in Canada, and is one of the oldest voices in reviewer-dom still publishing. He has done rather less of rum of late than of other spirits, and remains on this list for the same reason Dave Russell does – because his reviews of rums from before the Renaissance are a good resource and he covers Canada and North America better than most. Not so hot for the newer stuff or independents, though.

- PhilthyRum (Australia) – One of the few who posted about and from Australia, the site has not been updated since November 2018. What a shame.

News Sites and Newsletters

Not much news out there, the older sites have all been subsumed into the juggernaut that is Facebook. There do remain some holdouts that try to stem the tide of the Big Blue F and here are a few

- RumPorter – This site is in French, Spanish and English, and has both a paid and free section. The articles are well written and well researched and may be the best online magazine dealing with rum that is currently extant.

- Coeur de Chauffe (French) – Magazine-style deep-dive content, curated by Nico Rumlover (which I suspect is not his real name, but ok 🙂 ).

- Got Rum? – US-based ad-heavy magazine which publishes monthly. Paul Senft, one of the only remaining US rum reviewers left standing, posts his reviews here, and historical essays are provided by Marco Pierini. The rest is mostly news bits and pieces, of varying quality.

- The Rum Lab – There’s a website for this, with useful stuff like the Rum Connoisseur of the week, various infographics and news…my own preference is to subscribe to the newsletter which delivers it to your inbox every week. Good way to stay on top of the news if you don’t think FB is serving you up the rum related stories you like.

- *Added Instant Rum (French) – This is a magazine aggregator (i.e., no original content) which reposts sources and links of articles having to do with rum, in French. A lot of writers really hate the way it never asks for permission, and often doesn’t provide source attribution.

© istock.com/Rassco

Online Research, Technical, Background & History

Once you get deeper into the subculture, it stands to reason you’re going to want to know more, and social media is rarely the place for anyone who needs to go into the weeds and count the blades. And not everyone writes, or wants to write, or reads just about reviews, the latest rums, their rumfest visits – some like the leisurely examination of a subject down to the nth degree.

- Cocktail Wonk (now also the Rum Wonk) – Without question, freelance writer Matt Pietrek is the guy with the widest span of essays and longform pieces on technical and general aspects of the subject of rum, in the world. In his articles he has covered distillery visits and histories, technical production details, in-depth breakdowns and translations of governing regulations like GIs and the AOC, interviews and much more. Sooner or later, everyone who has a question on some technical piece of rum geekery lands on the rum section of this site.

- Rum Tasting Notes – Now renamed “Rum-X”. This is not a website, but a mobile application and is a successor to the lauded and much-missed site Reference Rhum. It is an app allowing you to input your tasting notes for whatever rums you are working with, to make a collection of your own and to curate it … but its real value lies in being a database, a reference of as many rums as can be input by its users. Last I checked in March 2022, there are over 12,000 rums in the library.

- WikiRum is another such app, but it differs in that it also has a fully functioning website in both French and English, and also with nearly 8,500 entries.

- American Distillery Index – Produced by Will Hoekenga (not the last time he turns up here) as part of the American Rum Report, it lists every distillery he could find in the USA by state, provides the website, a list of their rums and some very brief historical notes. There is an Australian Distillery Index that I use when doing research, but it’s not as well laid out.

- The Boston Apothecary – Very technical articles on distillation. The September 2020 article was called “Birectifier Analysis of Clairin Sajous,” so not airport bookstore material, if you catch my drift.

- Peter’ Rum Labels out of Czechoslovakia defies easy categorization. It’s one of the most unique rum-focused sites in existence, and the best for what it is: a compendium of pictures of labels from rum bottles. Ah, but there’s so much more: distillery and brand histories, obscure vintages and labels and producers….it’s an invitation to browse through rum’s history in a unique way that simply has no equal.

Sugar Lists

This is a subject that continues to inflate blood pressures around the world. Aside from the “wtf, is that true?” moments afflicting new rum drinkers, the most common question is “Does anyone have a list of rums that contain it?” Well, no. Nobody does. But many have hydrometer readings that translate into inferences as to the amount of additives (assumed to be sugar), and these are:

Podcasts

- Five minutes of rum – 88 (for now) short and accessible episodes about specific rums plus a bit of text background, some photos and cocktails. If time is of essence, here’s a place to go. Not updated since October 2021.

- Single Cast (French) – The big names of the Francophone rhum scene – Benoit Bail, Jerry Gitany, Laurent Cuvier, Christine Lambert, Roger Caroni – run these fortnightly podcasts, which make me despair at the execrable quality of my French language skills. Great content.

- Ralfy – Well, yes, Ralfy does do primarily whiskies on his eponymous vlog and rum takes a serious back seat. He does do rums occasionally, however, and his folksy style, easy banter, and barstool wisdom are really fun to watch (or just listen to), whether it’s in a rum review, or an opinion piece.

- Zavvy.co – A video platform which co-founders Federico Hernandez and Will Hoekenga (remember him from the American Rum Index?) intended as a live streaming tool for rum festivals, repurposed after COVID-19 shattered the world’s bar industry and cancelled all rumfests. Now it is a weekly series of interviews and discussions with members of the industry

- ACR has some really useful virtual distillery tours and “Rum Talk” sessions with distillery people

- Rumcast – This podcast run by John Gulla out of Miami and Will Hoekinga from Tennessee was very busy from April to August of 2020, then declined due to both the pandemic and the attention switching to Zavvy (Will Hoekinga is part of it, so that may be why). In 2021 the show went back up to a regular schedule of once a fortnight and passed their 50th podcast in March 2022. Very in-depth and knowledgeable interviews and occasionally just the two guys riffing on some rum related subject or other.

- Global Rum Room (FB) – This is a place where every Friday, rumfolk from around the world just hang out and sh*t talk, using a Zoom link. The link is usually posted weekly and to be found in the group page. It’s a private group, so an invitation is needed but as far as I know nobody has ever been turned away.

- *Added Romradion (English/Swedish): On Spotify, a Swedish site that often interviews English personages in the rum world. A mix of languages, good humoured, in depth, with an eclectic schedule and varying lengths – anywhere between twenty minutes and an hour. I like listening to them riff, though haven’t yet gone through all of their episodes.

Video Blogs

- Added Arminder Randhawa’s vlog Rum Revival on YouTube is one of the best shortform, easygoing video blogs out there. He keeps it clear, crisp and reasonably informative, doesn’t go on for too long and limits himself to themes and rum subjects that can take as little as three or four minutes, or as many as fifteen. Tight, quick editing, aimed squarely at those still early in their journey.

- Hugely enthusiastic and very short notes and reviews of mostly spiced rums come from the enormously entertaining and energetic Steve the Barman, which I would not normally include but nobody else is doing it to this extent and they need a home too. Steve rums both a YouTube channel and an Instagram Feed and goes all over the map with his quick videos. Unsurprisingly given his handle, his perspective is that of a barman, and one of knowledge sharing, not reviews so much

- Rum on the Couch – Dave Marsland, who runs the UK based Manchester Rum Festival, hosts brief conversational look-what-I-got videos and reviews of mostly one bottle at a time. He reminds me a lot of The Fat Rum Pirate’s informal written style. He really does, quite often, review from his couch. Lots of information and opinion presented in an easygoing fashion, and not as prolific as he once was, though still fun to watch any time he posts something.

- Ready Set Rum – A 2021-founded YouTube vlogger, Jamé Wills, is a Floridian originally from Trinidad (though his accent tilts more towards Jamaican on occasion). His rum video reviews are longer than most, and what characterizes them is his cheerful laid-back energy and the guests he brings in; the conversational back-and-forth makes each video a comfortable and fun watch. Also dropping in productivity as of 2023.

- Consider as well the videos of Scott Ferguson’s vlog “Different Spirits” (lots of rums reviews, some whiskies and other stuff, each about half an hour). He moonlights quite often on /r/rum on Reddit as a commentator and reviewer. The August 2022 episode “Introduction to Rum” is particularly good.

- The New World Rum Club – This was a new YouTube entrant, fresh out of the gate in January 2021. The Foursquare ECS overview is great (and doesn’t have a single tasting note). So far Simon concentrates on narratives, a gradually increasing amount of reviews, but alas, like others, less of late — nothing posted since November 2021.

- Diary of a Rum Hunter is too new for sweeping opinions about quality, for now. Darren has an armchair conversation and rum review thing going, but occasionally moves around in the real world to showcase the subject (as he did with the one about doubling his money on auctions). Each review, with one exception, is about 20-30 minutes. Hasn’t posted anything since December 2021.

Specific Articles

Specific Articles

Even within the fast moving rum community where things change on a daily basis, some articles stand out as being more than a flash in the pan and survive the test of time. Most bloggers content themselves with reviews and news, and a few go further into serious research or opinionating. Here some that bear reading:

- Tarquin (Rachel) Underspoon’s List of what Rums to Start With. Every boozer and every blogger sooner or later addresses this issue, and the lists change constantly depending on who’s writing it, and when. This is one of the best.

- The Cocktail Wonk’s article on E&A Scheer. This is the article that allowed laymen to understand what writers meant when they spoke about “brokers” buying bulk rum and then selling it to independent bottlers. It introduced the largest and oldest of them all, Scheer, to the larger public in an original article nobody else even thought to think about.

- The History of Demerara Distilleries, written by Marco Freyr of Germany, is the most comprehensive, heavily referenced, historically rigorous treatise on all the Guianese sugar plantations and distilleries ever written. No one who wants to know about what the DDL heritage still are all about can pass this monumental work by. The ‘Wonk has a two-part Cliff-notes version, here and here which is less professorial, based on his visits and interviews.

- Josh Miller’s well written piece on the development of Rhum Agricole.

- The Man With A Stroller, Laurent Cuvier, has, as of January 2022, a seriously good 12-part series of mini reviews exclusively dedicated to White Cane Juice Rums. You’ll have to use Google translate to convert the French (note: the link here goes to Part 12; links to the other 11 are at the bottom and he tells me there will undoubtedly be more to come)

- [Shameless plug alert!] The Age of Velier’s Demeraras. A favourite within my own writing, a deeply researched, deeply felt, three-part article on the impact Velier’s near-legendary Demerara rums had on the larger rumiverse. Two others are the History of the 151s, and the deep dive into all the different kinds of barrels and containers rum is and can be stored in.

Shopping Sites

Well, I can’t entirely ignore the question of “Where can I get…?” and get asked it more often than you might imagine. However, there are so many of sites nowadays, that I can’t really list them all. That said, here are some of the major ones I know of that other people have spoken about before. I’ll add to them as I try more, or get recommendations from readers.

(Note: listing them here is not an endorsement of their prices, selections or shipping policies; nor have I used them all myself, and they may not ship to you).

USA

EU & UK

Canada

The Final Question

The Final Question

I wanted to address the one question that comes up in my private correspondence perhaps more often even than “Where can I find…?” or “Have you tried…?”.

And that’s “How much is this bottle worth?”

Aside from the trite response of It’s worth whatever someone is willing to pay, there is no online answer, and I know of no resource that provides it as a service outside of an auction house or a site like RumAuctioneer where the public will respond by bidding, or not. One can, of course, always check on the FB rum fora above, post a picture and a description and ask there, and indeed, that is nowadays as good a method as any. Outside that, don’t know of any.

So, that said, I never provide a website resource or give a numerical answer, and my response is always the same: “It is worth drinking.”

Summing up

When I look down this listing of online resources (and below in the books section), I am struck by what an enormous wealth of information it represents, what an investment of so many people’s time and effort and energy and money. The commitment to produce such a cornucopia of writing and talking and resources, all for free, is humbling.

In the last fourteen years since I began writing, we have seen the rise of blogs, published authors, rum festivals, and websites, even self-bottlings and special cask purchases by individuals who just wanted to pass some stuff around to friends and maybe recover a buck or two. New companies sprung up. New fans entered the field. Rum profiles and whole marketing campaigns changed around us. The thirst for knowledge and advice became so great that a veritable tsunami of bloggers rose to meet the challenge – not always to educate the eager or sell to the proles, but sometimes just to share the experience or to express a deeply held opinion.

It’s good we have that. In spite of the many disagreements that pepper the various discussions on and offline, the interest and the passion about rum remains, and results in a treasure trove of online resources any neophyte can only admire and be grateful for. As I do, and I am.

Appendix – Books On Rum

Appendix – Books On Rum

Books are not an online resource per se, so I chose to put them in as an appendix. I do however believe they have great value as resources in their own right, and not everything that is useful to an interested party can always be found online.

Unsurprisingly, there is no shortage of reference materials in the old style format. No matter how many posts one has, how many essays, how many eruditely researched historical pieces or heartbreaking works of staggeringly unappreciated genius, there’s still something about saying one has published an actual book that can’t be beat. Here’s a few that are worth reading (and yes, I know there are more):

- Rums of the Eastern Caribbean (Ed Hamilton) – Released in 1995 at the very birth of the modern rum renaissance, this book was varied survey of as many distilleries and rums as Mr. Hamilton found the time to visit over many years of sailing around the Caribbean. Out of print and out of date, it’s never been updated or reprinted. Based on solid first hand experience of the time (1990s and before), and many rum junkies who make distillery trips part of their overall rum education are treading in his footsteps. (It was followed up in 1997 by another book called “The Complete Guide to Rum”).

- Rum (Dave Broom) – This 2003 book combined narrative and photographs, and included a survey of most of the world’s rum producing regions to that time. It was weak on soleras, missed independents altogether and almost ignored Asia, but had one key new ingredient – the introduction and codification of rum into styles: Jamaican, Guyanese, Bajan, Spanish and French island (agricole). Remains enormously influential, though by now somewhat dated and overtaken by events (he issued a follow-up “Rum: The Manual” in 2016, the same year as “Rum Curious” by Fred Minnick came out).

Atlas Du Rhum (Luca Gargano) – A coffee-table sized book that came out around 2014. Unfortunately only available in Italian and French for now. It’s a distillery by distillery synopsis of almost every rum making facility in the Caribbean and copies the format of Broom’s book and the limited focus of Hamilton’s, and does it better than either. Beautifully photographed, full of historical and technical detail. Hopefully it gets either a Volume 2 or an update for this decade, at some point, and FFS let’s have an English edition!

Atlas Du Rhum (Luca Gargano) – A coffee-table sized book that came out around 2014. Unfortunately only available in Italian and French for now. It’s a distillery by distillery synopsis of almost every rum making facility in the Caribbean and copies the format of Broom’s book and the limited focus of Hamilton’s, and does it better than either. Beautifully photographed, full of historical and technical detail. Hopefully it gets either a Volume 2 or an update for this decade, at some point, and FFS let’s have an English edition!- French Rum – A History 1639-1902 (Marco Pierini). This is one of those books that should be longer, just so we can see what happened after Mont Pelee erupted in 1902. Still, let’s not be ungrateful. Going back into the origins of distilled spirits and distillation in the Ancient World, Marco slowly and patiently traces the evolution of rum, and while hampered by a somewhat professorial and pedantic writing style, it remains a solid work of research and scholarship.

The Silent Ones (Cyril Weglarz) – Few books about rum’s subculture impressed and moved me as much as Cyril’s. In it, he toured the Caribbean islands (on his own dime), and interviewed the people we never hear about: the workers, those in the cane field, the lab, the distillery. And provided a portrait of these silent and unsung people, allowing us to see beyond superstar ambassadors and producers, to the things these quieter people do and the lives they lead.

The Silent Ones (Cyril Weglarz) – Few books about rum’s subculture impressed and moved me as much as Cyril’s. In it, he toured the Caribbean islands (on his own dime), and interviewed the people we never hear about: the workers, those in the cane field, the lab, the distillery. And provided a portrait of these silent and unsung people, allowing us to see beyond superstar ambassadors and producers, to the things these quieter people do and the lives they lead.- Smuggler’s Cove: Exotic Cocktails, Rum, and the Cult of Tiki (Martin & Rebecca Cate) – Addressed to the cocktail and tiki crowd in 2016 (as is self evident from the title) the reason I include this book here is because of the Cates’ proposal for another method classification for rums that goes beyond the too-limited styles of Dave Broom, and is perhaps more accessible than the technical rigour of the one suggested by Luca Gargano. Jury is still out there. Other than that, just a fun read for anyone into the bar and mixing scene.

- Minimalist Tiki (Matt Pietrek) – If I include one, I have to include the other. Matt self published his book about matters tiki in 2019, and again, it is a book whose subject is obvious. Except, not really – the section about rum, its antecedents and background, the summing up of the subject to 2019, is really very well done and pleasantly excessive, maybe ⅓ of the whole thing. The photos are great and I’m sure to learn a thing or two about mixing drinks in the other ⅔. For now, it’s the bit about rum I covet.

Rum Curious (Fred Minnick) – Building on the previous book by the Cates, this takes rum in its entirety as its subject, and covers history, production, regulations, tastings, cocktails and more. It’s a great primer for any beginner, still recent enough to be relevant (many of the issues it mentions, like additives, disclosure, labelling, regulations, remain hotly debated to this day), though occasionally dated with some of the rums considered top end, and very weak in global rum brands from outside the Caribbean.

Rum Curious (Fred Minnick) – Building on the previous book by the Cates, this takes rum in its entirety as its subject, and covers history, production, regulations, tastings, cocktails and more. It’s a great primer for any beginner, still recent enough to be relevant (many of the issues it mentions, like additives, disclosure, labelling, regulations, remain hotly debated to this day), though occasionally dated with some of the rums considered top end, and very weak in global rum brands from outside the Caribbean.- And a Bottle of Rum: A History of the New World in Ten Cocktails (Wayne Curtis) – This is a book about rum, cocktails and American history. It is not for getting an overview of the entire rum industry or the issues that surround it, or any kind of tasting notes or reviews. But it is an enormously entertaining and informative read, and you’ll pick up quite a bit around the margins that cannot but increase your appreciation for the spirit as a whole.

- A Jamaican Plantation: The History of Worthy Park 1670-1970 (Michael Craton & James Walvin) – A deep dive into the history of one of the best known Jamaican distilleries. (I’m sure there are others that speak to other distilleries and plantation, but this is the one I happen to have, and have read).

- The Distillers Guide to Rum (Ian Smiley, Eric Watson, Michael Delevante) – For a book that came out in 2013, it remains useful and not yet dated. As its title indicates, it is about distillation methodology, and there is some good introductory rum material as well. If you want to know about equipment, ingredients, fermentation, blending, vatting, maturation, that’s all there – and then there’s supplementary stuff about the subject (styles, bars, cocktails, etc) as well, making it a useful book for anyone who wants to know more about that aspect of the subject.

*Added Modern Caribbean Rum (Matt Pietrek and Carrie Smith) – Published in late 2022, this book is sure to remain a standard reference for the next decade (at least). It tries to cover everything: history, production, technical details, the rum business, regulations, and biographies of just about all the Caribbean distilleries. It’s not small and it’s not light, but as a roundup of a bunch of rum geekery — in essence, every question a neophyte or an interested rum geek might have — is covered. (Note: There are no rum reviews here, which I think was the right decision – something would always be left out and the releases these days are so quick and so numerous that the book would be dated for such a section even by the time it went on sale).

*Added Modern Caribbean Rum (Matt Pietrek and Carrie Smith) – Published in late 2022, this book is sure to remain a standard reference for the next decade (at least). It tries to cover everything: history, production, technical details, the rum business, regulations, and biographies of just about all the Caribbean distilleries. It’s not small and it’s not light, but as a roundup of a bunch of rum geekery — in essence, every question a neophyte or an interested rum geek might have — is covered. (Note: There are no rum reviews here, which I think was the right decision – something would always be left out and the releases these days are so quick and so numerous that the book would be dated for such a section even by the time it went on sale).

The Rum Barrel Blog

The Rum Barrel Blog The Rums of the Man With the Stroller

The Rums of the Man With the Stroller Who Rhum the World?

Who Rhum the World?

Rum Gallery

Rum Gallery

Atlas Du Rhum (Luca Gargano)

Atlas Du Rhum (Luca Gargano) The Silent Ones (Cyril Weglarz)

The Silent Ones (Cyril Weglarz) Rum Curious (Fred Minnick)

Rum Curious (Fred Minnick)